The Expanding Horizon: American Music at 250

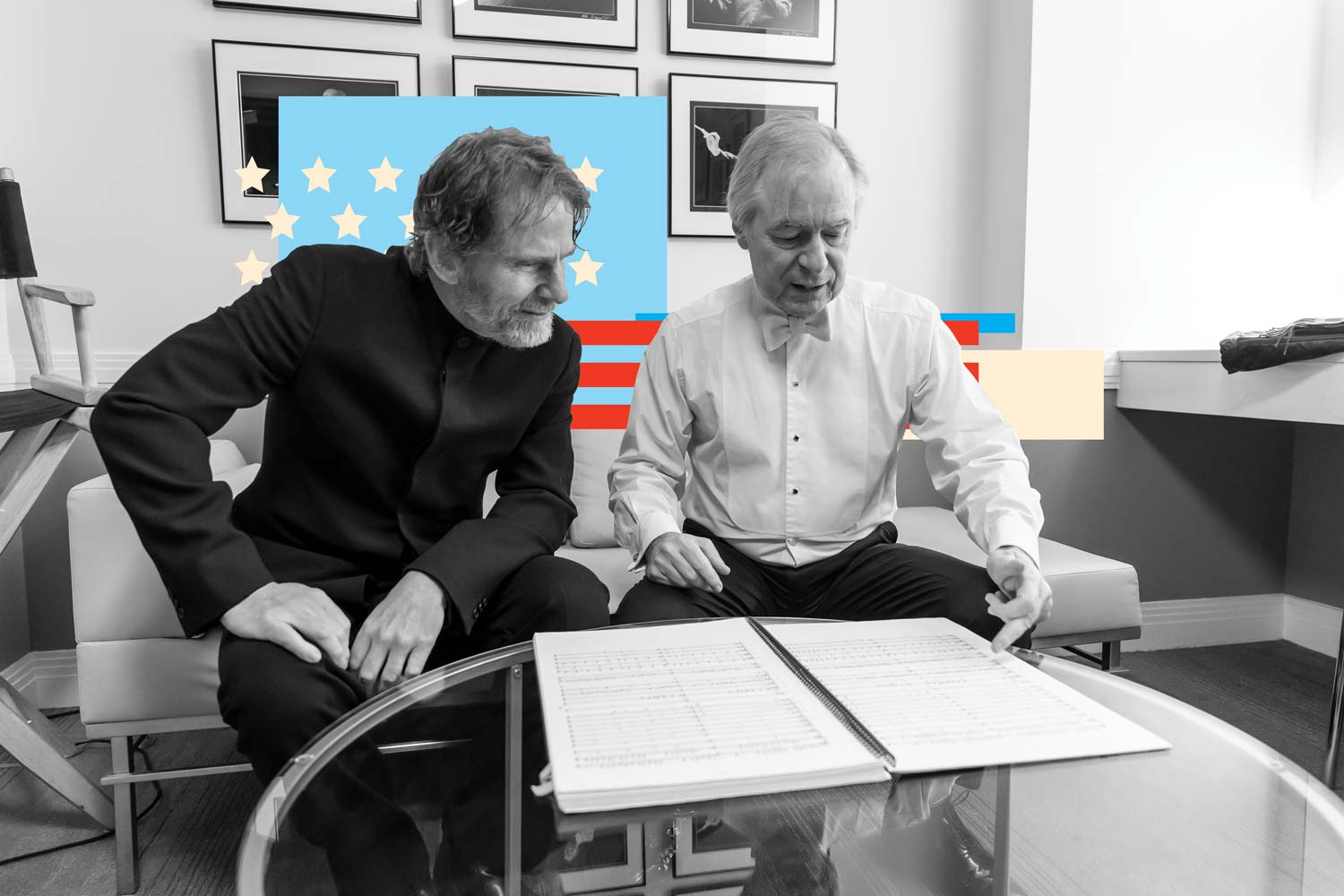

An Introduction by David Robertson

“The freedom found in American music helped break down restrictive boundaries.”

Nowadays, as a conductor I often present works to orchestras and audiences where American music is not native. This sometimes seems a strange juxtaposition: John Adams in Beijing and Helsinki, Samuel Barber in London and Lyon, Leonard Bernstein in Aalborg and Warsaw, John Cage in Torino and Paris, Elliott Carter in Amsterdam and Munich, Aaron Copland in Kilkenny and Jerusalem, Natalie Dietterich in Luxemburg, Morton Feldman in Edinburgh and Cologne, George Gershwin in Genoa and Montpellier, Charles Ives in Tongyeong and Budapest, Steven Mackey in Vienna and Sydney, Steve Reich in Metz and Munich, Christopher Rouse in Sydney, Frederic Rzewski and Ruth Crawford Seeger in Paris. What do all these composers have in common? Why look to American music?

The story of music in the United States began well before the signing of the Declaration of Independence. Our great melting pot of peoples and cultures has known contributions from those who were native to the land, those who came of their free will, and those who were brought by coercion. They all have had a hand in creating this enormous E pluribus unum called American music.

“On the long road to a more perfect union, we are heartened to hear ‘there’s a place for us.’”

The staggering variety of sounds defies adequate description. It starts with song: voices from the heart, trained and untrained, all influencing a breaking down of barriers between work-song and worship, entertainment and artistic aspiration. The open frontier leads to the idea that anything is possible in such a vast land. This independent spirit was beautifully expressed in 1770 by the New Englander William Billings, a tanner by day and songsmith by night: “I don’t think myself confin’d to any Rules for Composition laid down by any that went before me.” It is not hard to see a family resemblance to Charles Ives, Carl Ruggles, Henry Cowell, Harry Partch, John Cage, Conlon Nancarrow, Alvin Lucier, La Monte Young, Pauline Oliveros, and Tod Machover.

America itself is a concept, a continual becoming, experimenting, innovating. This idea of building a better, more perfect union extends to music. Two co-signers of that 1776 declaration, Benjamin Franklin and Francis Hopkinson, worked respectively on building the glass harmonica and improving harpsichord quills by making them out of leather. Inventing, seeing new possibilities, realizing dreams leads one right to Henry Steinway’s pianos, Laurens Hammond’s organs, Leo Fender’s guitars, Robert Moog’s modular synthesizer, or John Chowning’s FM synthesis.

Duke Ellington and Billy Strayhorn had it right when they said: “It don’t mean a thing if it ain’t got that swing!” The physical nature of movement, rhythm’s reign, the dancing body, the tightrope walk of larynx and lips, has meant that the vernacular with all its variations is right at the center of our musical syntax. These cadences make possible Laurie Anderson, Steve Reich, Leonard Bernstein, Meredith Monk, John Adams, Robert Ashley, and Steven Mackey, among many others.

A unique cross-fertilization of endeavors enriches our complex, often frustrating history. Seven days before the horrific Tulsa race massacre of 1921, the Broadway opening of Shuffle Along, an all-Black musical composed by Eubie Blake and Noble Sissle, transformed how all musical theater would be made in America. In the 1930s era of segregation, Benny Goodman was one of the first musicians to break through that noxious notion, the constitution of his band based on talent alone. At a time when the world was at war and the US was confining Japanese Americans in camps, Martha Graham chose Isamu Noguchi to design the sets for her ballet with Aaron Copland, performed right in Washington, D.C. On the long road to a more perfect union, we are heartened to hear “there’s a place for us.”

The grand story of America is that it is being created constantly, connected to its past, but forging forward into a future unknown. Performing, exploring the American musical landscape can lead to unexpected inspiration, questioning contemplation, and the awareness that self-evident truths are anything but that.

©2023 David Robertson